Transfer Pricing in the United States: A Practical Guide

Introduction

Transfer pricing (TP) is a critical issue for multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in or planning an investment in the United States. With the increasing scrutiny from tax authorities internationally and the complexity of the U.S. tax system, it is essential for MNEs to have a solid understanding of U.S. transfer pricing regulations and best practices. This white paper provides an overview of US TP rules and practical steps for navigating the US TP landscape.

Overview of U.S. Transfer Pricing Regulation

The U.S. transfer pricing statute is expressed in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 482. This section grants the IRS the authority to allocate income, deductions, credits, or allowances among related parties to prevent tax evasion and ensure that taxpayers clearly reflect income attributable to controlled transactions. Section 482 applies to all controlled transactions and covers the sale of goods, provision of services, licensing of intangibles, and financing arrangements.

Section 482 generally provides that prices charged by one affiliate to another yield results that are consistent with the results that would have been realized if uncontrolled taxpayers had engaged in the same transaction under the same circumstances. This principle, known as the arm’s length principle, has become the internationally accepted standard for evaluating intercompany pricing.

To illustrate the arm’s length principle, suppose a U.S. Parent sells a product to its commonly controlled Canadian distributor. This sale is a controlled transaction. Under Section 482, the controlled transaction should be priced in the same way that an uncontrolled transaction would be priced under similar circumstances. The price that the U.S. Parent charges its distributor should be the same as it would charge to an unrelated party under similar circumstances.

Treasury Regulation §1.482 provides specific rules, guidance, and examples for applying IRC Section 482. The regulations provide considerable detail on selecting the best method, making comparability adjustments, and determining the arm’s length result under the various transfer pricing methods.

The U.S. has led the way in legislation of transfer pricing regulations. The OECD, as a means of providing guidelines for the rest of the world, subsequently issued its own OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines. The latest revision to the OECD Guidelines was in January 2022. The OECD Guidelines are generally consistent with the U.S. TP rules, though some differences do exist.

Penalties for increases in U.S. corporate income tax attributable to Section 482 adjustments are substantial. IRC 6662(e) sets the penalty equal to 20% of the underpayment of tax attributable to substantial valuation misstatements. Under IRC Section 6662(h), the penalty increases to 40% of the underpayment for a gross valuation misstatement. Substantial valuation misstatements occur when the taxpayer’s price is 200% or more (or 50% or less) than the correct price, and gross valuation misstatements occur when the price is 400% or more (or 25% or less) than the correct amount.

The taxpayer’s best strategy for avoiding noncompliance is to use reasonable transfer pricing methods and prepare adequate documentation.

Economic Analysis & Transfer Pricing Methods

As noted earlier, Treasury Regulation §1.482 provides the foundational concepts for transfer pricing analysis. In practice, transfer pricing analyses involve the following steps:

- Determining if control indeed exists

- Determining what type of controlled transaction(s) exists

- Determining what legal entity will be the tested party

- Selecting the best transfer pricing method

- Selecting benchmark prices, transactions, or more generally “comparables”

- Making comparability adjustments and constructing the arm’s length range

- Applying the arm’s length range to the tested party (the controlled transaction or entity)

- Taking action if the tested party results are outside the range

- Preparing the necessary documentation

Control. Without common control, no transfer pricing issue exists. In the U.S., control is broadly defined and can exist through equity ownership, contractual arrangements, or even de facto circumstances where one party has practical influence over the other. U.S. courts have found common control in situations involving less than 50% equity ownership. And control is assumed if income or deductions have been shifted arbitrarily.

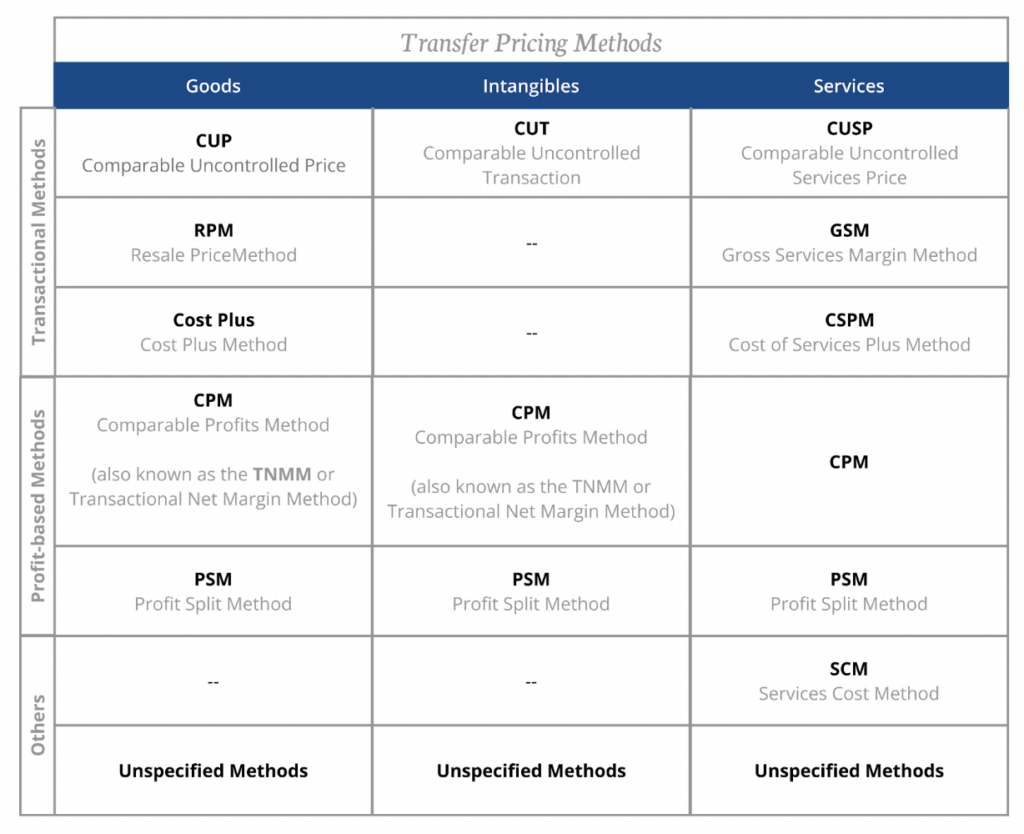

Controlled transactions. The type of controlled transaction(s) determines which TP methods are most appropriate. Different TP methods are used for the transfer of goods, provision of services, licensing or sale of intangibles, and intercompany financing arrangements.

Tested party. Transfer pricing methods typically compare the results of one of the controlled entities (the tested party) against those of the uncontrolled parties (the comparables). U.S. regulations provide that the tested party should have the most reliable data and comparables. The tested party is often more straightforward, less entrepreneurial, and owns no valuable intangible assets or IP. Commonly tested parties include distributors, contract manufacturers, and service companies.

Best method. The U.S. regulations require the use of the most reliable method (i.e., the Best Method) for measuring the arm’s length range. Key factors determining the Best Method include the comparability between controlled and uncontrolled transactions and the reliability of the data. Taxpayers are encouraged to consider all the acceptable TP methods, but in practice, the Best Method rule typically results in only the most reliable method being applied.

Selecting benchmarks. Constructing the arm’s length range is accomplished by selecting comparables, adjusting them, and benchmarking their results. This step is frequently referred to as “economic analysis.” Because regulations place a high value on comparability and data quality, TP specialists conduct “functional, asset, and risk analysis” (functional analysis or FAR analysis) to evaluate factors that affect the pricing of controlled and uncontrolled transactions. The factors assessed include functions the entities perform, resources used, contractual terms, risks assumed, economic conditions, and ownership/use of intangibles.

- Functional analysis. Robust functional analysis results in selecting comparables that are economically similar to the tested party. Comparables often, but not always, share industry and product similarities with the tested party. The comp set may be further refined by evaluating various financial metrics (R&D as a percentage of sales, S&M as a percentage of sales, customer concentration, etc.) and other criteria. This process requires professional judgment and access to specialized financial databases.

- Comparability adjustments. The next step in economic analysis is to apply adjustments that enhance the comparability of the controlled and uncontrolled transactions. Typical adjustments include adjustments for inventory valuation methods, amortization of intangibles, working capital, currency risk, etc. This is a critical step requiring the help of transfer pricing experts as many tax examinations focus on issues of comparability.

- Arm’s length range. The final step is benchmarking the comparables’ results. For clarity, the result is a metric such as gross margin, operating profit margin, or Berry ratio, among others. The results are typically benchmarked using a statistical method known as the interquartile range (IQR). The IQR measures the middle 50% of a dataset by calculating the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile of a data range. An example IQR of the net cost plus (NCP) for management consulting service providers is below:

If the comparables and controlled transaction are very similar, and no material adjustments are made to the comparables, the use of the entire range may be appropriate. However in practice, the IQR is the most commonly used range.

- Applying the arm’s length range. The tested party’s results are compared against the arm’s length range. For example, suppose the Comparable Profit Method (CPM) was used to determine an arm’s length operating profit margin range of 2% to 4%. The tested party’s operating profit margin is 3%, which is within the range; therefore, no adjustments are needed.

- Results outside the range. If, however, the tested party’s operating profit margin is 1%, this would be outside of the range and necessitate an adjustment. In this case, the taxpayer could revisit the transfer pricing analysis to determine if any reasonable adjustments can be made to place the tested party results within the range prior to the submission of the U.S. tax return (M-1 adjustment). Alternatively, the taxpayer can adjust its operations to bring the tested party results within the range.

- Documentation. Finally, U.S. regulations offer protections for taxpayers with contemporaneous documentation of their TP analysis. This documentation, often called a Transfer Pricing Study, will be discussed in more detail.

- The above steps form the basics of every transfer pricing analysis, but U.S. regulations acknowledge certain circumstances that impact transfer pricing. These special circumstances are beyond the scope of this white paper, but include the pursuit of market penetration strategies, relocating operations to lower-cost territories, and blocked income.

United States Documentation Requirements

Although U.S. statute does not require the preparation of TP documentation, penalty rules and other countries’ standards make documentation a de facto requirement. For example, in the event of an examination, regulations condition the taxpayer to provide documentation to the IRS within 30 days of request, and the documentation must exist when the U.S. tax return is filed. It is advisable to view documentation in the U.S. as both a planning tool and a shield protecting from adverse adjustments.

Principal documents. Treas. Reg. § 1.6662-6(d)(2)(iii)(B) sets forth the “principal documents” that must be maintained by a taxpayer to satisfy a documentation request. The principal documents include:

- An overview of the taxpayer’s business, including an analysis of the economic and legal factors that affect the pricing of its property or services;

- A description of the taxpayer’s organizational structure (including an organization chart) covering all related parties engaged in transactions potentially relevant under section 482, including foreign affiliates whose transactions directly or indirectly affect the pricing of property or services in the United States;

- Any documentation explicitly required by the regulations under section 482;

- A description of the method selected and an explanation of why that method was selected, including an evaluation of whether the regulatory conditions and requirements for application of that method, if any, were met;

- A description of the alternative methods that were considered and an explanation of why they were not selected;

- A description of the controlled transactions (including the terms of sale) and any internal data used to analyze those transactions;

- A description of the comparables that were used, how comparability was evaluated, and what (if any) adjustments were made;

- An explanation of the economic analysis and projections relied upon in developing the method;

- A description or summary of any relevant data that the taxpayer obtains after the end of the tax year and before filing a tax return, which would help determine if a taxpayer selected and applied a specified method in a reasonable manner; and

- A general index of the principal and background documents and a description of the recordkeeping system used for cataloging and accessing those documents.

Although the U.S. has not implemented the OECD concepts of a Master File and a Local File, IRS practice units regard principal documentation requirements as equivalent to those of Master Files and Local Files. These documents, which provide a global overview of a multinational group (master file), and details specific to controlled transactions in a given country (local file), are often prepared separately but in conjunction with a US TP study to meet the multinational’s full requirements per foreign jurisdiction legislation.

The U.S. has adopted the OECD concept of country-by-country (CbC) reporting for MNEs with annual group revenues greater than $850 million. CbC reports summarize income, earnings, taxes paid, and economic activity on a country-by-country basis. These reports are intended to promote transparency and help tax authorities identify potential transfer pricing risks for further investigation.

Large multinationals with ever-evolving operations (acquisitions, divestments, development of valuable IP) are encouraged to prepare U.S. contemporaneous documentation annually. Smaller taxpayers should work with their advisors to understand how to meet requirements cost-effectively.

Advanced Pricing Agreements

The largest taxpayers with the greatest potential exposure have an additional tool: Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs). APAs provide a proactive way for companies to manage transfer pricing risks by securing advance agreement from tax authorities on the appropriate transfer pricing methodology for their intercompany transactions. APAs offer certainty, reduce the risk of double taxation, and minimize the likelihood of costly transfer pricing audits and disputes.

The number of APAs filed with the IRS each year has trended upward since 2019, with approximately 150 APAs filed and completed each year. On average, APAs take 2 to 4 years to complete, with unilateral (U.S.-only) and renewal APAs taking less time, and multilateral (U.S. plus a treaty partner) and new APAs taking more time. APAs typically have a term of 5 to 7 years, but lengths vary.

Most APA filers are large manufacturers and wholesale retailers, but service providers and financial services companies are also represented. The top countries involved in bilateral APAs include Japan, India, Italy, and Canada.

APAs are a valuable tool for the largest and most sensitive taxpayers. But given the investment in time, management attention, and budget (application fees alone are over $50K for small filers and $100K for large filers), the vast majority of MNEs do not pursue them as a strategy.

Intangible Property Transactions in the United States

Intangible property (IP) transactions present unique transfer pricing challenges. IP assets include patents, trademarks, copyrights, brand names, and proprietary technology. These assets drive significant value for companies but can be complex to price from a TP perspective because they have no physical presence and often lack comparable transactions. Tax authorities worldwide, including the U.S., are concerned about multinationals shifting IP ownership to low-tax countries and paying royalties for IP use in high-tax countries.

This concern is not unfounded. Research has found that tax havens hold a disproportionately large amount of IP compared to the IP generated by their residents. A 2022 analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis revealed that in Bermuda, which had a 0% corporate income tax rate until 2025, 38 foreign patent applications were submitted for every patent application filed by a Bermudian inventor. 96% of foreign patent applications came from multinational corporations.

The IRS has taken steps to encourage multinationals that have transferred IP abroad to repatriate those assets back to the U.S. Recently adopted updates to Section 367(d) of the IRC create opportunities for tax-free IP repatriation while also reducing the risk of excessive taxation related to IP.

Comprehensive IP analysis is often the first step in transfer pricing for multinationals with high-value IP, completing M&A or reorganization transactions involving IP, or holding IP in multiple jurisdictions. Working with international tax counsel and IP valuation experts can present tax efficiency opportunities while also mitigating the risk of IRS challenges and double taxation.

Transfer Pricing Audits & Disputes

Transfer pricing scrutiny is on the rise, and multinational CFOs frequently report TP audits and penalties as one of their top concerns. TP audits are expensive and time-consuming, often taking years to resolve. And for taxpayers that fail to defend their positions, the penalties can be massive. As of the publishing of this white paper, Microsoft is currently under an IRS audit related to TP in which the additional tax payment (plus penalties and interest) is nearly $29 billion. While smaller multinationals face lower stakes, all taxpayers are compelled to minimize audit risk.

In the U.S., the audit process typically begins with an information request from the IRS, followed by a detailed examination of the taxpayer’s transfer pricing documentation and intercompany transactions. The IRS may propose adjustments if it determines that the transfer prices do not reflect arm’s length pricing.

The first and best defense is maintaining robust contemporaneous documentation. CFOs and Tax VPs concerned about tax liability can also conduct periodic pre-audit reviews and may consider making voluntary disclosures demonstrating a good faith effort towards compliance.

Competent Authority and Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP). When transfer pricing adjustments lead to double taxation, taxpayers may seek relief through the Competent Authority process and Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP). These procedures, outlined in tax treaties, allow taxpayers to request that the competent authorities of the relevant countries (e.g., the IRS in the U.S. and the CRA in Canada) negotiate to eliminate double taxation. The U.S. Competent Authority has a strong track record of resolving transfer pricing disputes through MAP, providing taxpayers with an effective means of mitigating the impact of transfer pricing adjustments.

Conclusions & Practical Steps

Transfer pricing is not merely a compliance exercise but an integral part of global business strategy. As MNEs navigate the complex and ever-changing transfer pricing landscape, they must proactively manage their TP policies to minimize risks and optimize tax outcomes. This is particularly crucial for companies doing business in the United States or contemplating an investment in the U.S., given the country’s robust transfer pricing regulations and enforcement environment.

To effectively manage transfer pricing in the U.S., MNEs should work closely with experienced international tax counsel and transfer pricing economists. These professionals can provide guidance and support throughout the transfer pricing lifecycle, from planning and implementation to compliance and dispute resolution. Key matters include legal entity selection and formation, strategizing corporate functions and asset ownership, preparing TP analysis and documentation, drafting intercompany agreements, and defending pricing under examination.

By taking a proactive and strategic approach to transfer pricing, MNEs will be well-positioned for commercial success in the United States and beyond.

Contact Our Transfer Pricing Team

For more information or to request a consultation, please contact our international team of transfer pricing specialists:

Samuel Scott

Jared Christian

cameron.smith@scalar.io

Jonathan Lubick

jonathan.lubick@scalar.io

Transfer Pricing Abbreviations & Acronyms

| APA | Advance Pricing Agreement |

| APMA | Advance Pricing and Mutual Agreement Program |

| ALS | Arm’s Length Standard |

| BEPS | Base Erosion and Profit Shifting |

| CbCR | Country-by-Country Reporting |

| CCA | Cost Contribution Arrangement |

| CFC | Controlled Foreign Corporation |

| CPM | Comparable Profits Method |

| CSA | Cost Sharing Arrangement |

| CUP | Comparable Uncontrolled Price |

| DEMPE | Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection, and Exploitation |

| FTC | Foreign Tax Credit |

| GILTI | Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income |

| IP | Intangible Property or Intellectual Property |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IRC | Internal Revenue Code |

| IRS | Internal Revenue Service |

| MAP | Mutual Agreement Procedure |

| MNE | Multinational Enterprise |

| NCP | Net Cost Plus |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PE | Permanent Establishment |

| PLI | Profit Level Indicator |

| PSM | Profit Split Method |

| QCSA | Qualified Cost Sharing Arrangement |

| R&D | Research & Development |

| RPM | Resale Price Method |

| S&M | Sales & Marketing |

| TNMM | Transactional Net Margin Method |

| TP | Transfer Pricing |

| TPM | Transfer Pricing Method |

| TPRA | Transfer Pricing Risk Assessment |

| USPTO | United States Patent and Trademark Office |

Glossary of Key Terms

The following glossary is provided in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. OECD (2022), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0e655865-en.

Advance pricing arrangement (APA)

An arrangement that determines, in advance of controlled transactions, an appropriate set of criteria (e.g. method, comparables and appropriate adjustments thereto, critical assumptions as to future events) for the determination of the transfer pricing for those transactions over a fixed period of time. An advance pricing arrangement may be unilateral involving one tax administration and a taxpayer or multilateral involving the agreement of two or more tax administrations.

Arm’s length principle

The international standard that OECD member countries have agreed should be used for determining transfer prices for tax purposes. It is set forth in Article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention as follows: where “conditions are made or imposed between the two enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which would be made between independent enterprises, then any profits which would, but for those conditions, have accrued to one of the enterprises, but, by reason of those conditions, have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly”.

Arm’s length range

A range of figures that are acceptable for establishing whether the conditions of a controlled transaction are arm’s length and that are derived either from applying the same transfer pricing method to multiple comparable data or from applying different transfer pricing methods.

Associated enterprises

Two enterprises are associated enterprises with respect to each other if one of the enterprises meets the conditions of Article 9, sub-paragraphs 1a) or 1b) of the OECD Model Tax Convention with respect to the other enterprise.

Balancing payment

A payment, normally from one or more participants to another, to adjust participants’ proportionate shares of contributions, that increases the value of the contributions of the payer and decreases the value of the contributions of the payee by the amount of the payment.

Buy-in payment

A payment made by a new entrant to an already active CCA for obtaining an interest in any results of prior CCA activity.

Buy-out payment

Compensation that a participant who withdraws from an already active CCA may receive from the remaining participants for an effective transfer of its interests in the results of past CCA activities.

Comparability analysis

A comparison of a controlled transaction with an uncontrolled transaction or transactions. Controlled and uncontrolled transactions are comparable if none of the differences between the transactions could materially affect the factor being examined in the methodology (e.g. price or margin), or if reasonably accurate adjustments can be made to eliminate the material effects of any such differences.

Comparable uncontrolled transaction

A comparable uncontrolled transaction is a transaction between two independent parties that is comparable to the controlled transaction under examination. It can be either a comparable transaction between one party to the controlled transaction and an independent party (“internal comparable”) or between two independent parties, neither of which is a party to the controlled transaction (“external comparable”).

Comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method

A transfer pricing method that compares the price for property or services transferred in a controlled transaction to the price charged for property or services transferred in a comparable uncontrolled transaction in comparable circumstances.

Compensating adjustment

An adjustment in which the taxpayer reports a transfer price for tax purposes that is, in the taxpayer’s opinion, an arm’s length price for a controlled transaction, even though this price differs from the amount actually charged between the associated enterprises. This adjustment would be made before the tax return is filed.

Contribution analysis

An analysis used in the profit split method under which the relevant profits from controlled transactions are divided between the associated enterprises based upon the relative value of the contributions made by each of the associated enterprises participating in those transactions, supplemented where possible by external market data that indicate how independent enterprises would have divided profits in similar circumstances.

Controlled transactions

Transactions between two enterprises that are associated enterprises with respect to each other.

Corresponding adjustment

An adjustment to the tax liability of the associated enterprise in a second tax jurisdiction made by the tax administration of that jurisdiction, corresponding to a primary adjustment made by the tax administration in a first tax jurisdiction, so that the allocation of profits by the two jurisdictions is consistent.

Cost contribution arrangement (CCA)

A CCA is a contractual arrangement among business enterprises to share the contributions and risks involved in the joint development, production or the obtaining of intangibles, tangible assets or services with the understanding that such intangibles, tangible assets or services are expected to create benefits for the individual businesses of each of the participants.

Cost plus mark-up

A mark-up that is measured by reference to margins computed after the direct and indirect costs incurred by a supplier of property or services in a transaction.

Cost plus method

A transfer pricing method using the costs incurred by the supplier of property (or services) in a controlled transaction. An appropriate cost plus mark-up is added to this cost, to make an appropriate profit in light of the functions performed (taking into account assets used and risks assumed) and the market conditions. What is arrived at after adding the cost plus mark up to the above costs may be regarded as an arm’s length price of the original controlled transaction.

Direct-charge method

A method of charging directly for specific intra-group services on a clearly identified basis.

Direct costs

Costs that are incurred specifically for producing a product or rendering service, such as the cost of raw materials.

Functional analysis

The analysis aimed at identifying the economically significant activities and responsibilities undertaken, assets used or contributed, and risks assumed by the parties to the transactions.

Global formulary apportionment

An approach to allocate the global profits of an MNE group on a consolidated basis among the associated enterprises in different jurisdictions on the basis of a predetermined formula.

Gross profits

The gross profits from a business transaction are the amount computed by deducting from the gross receipts of the transaction the allocable purchases or production costs of sales, with due adjustment for increases or decreases in inventory or stock-in-trade, but without taking account of other expenses.

Independent enterprises

Two enterprises are independent enterprises with respect to each other if they are not associated enterprises with respect to each other.

Indirect-charge method

A method of charging for intra-group services based upon cost allocation and apportionment methods.

Indirect costs

Costs of producing a product or service which, although closely related to the production process, may be common to several products or services (for example, the costs of a repair department that services equipment used to produce different products).

Intra-group service

An activity (e.g. administrative, technical, financial, commercial, etc.) for which an independent enterprise would have been willing to pay or perform for itself.

Intentional set-off

A benefit provided by one associated enterprise to another associated enterprise within the group that is deliberately balanced to some degree by different benefits received from that enterprise in return.

Marketing intangible

An intangible (within the meaning of paragraph 6.6) that relates to marketing activities, aids in the commercial exploitation of a product or service and/or has an important promotional value for the product concerned. Depending on the context, marketing intangibles may include, for example, trademarks, trade names, customer lists, customer relationships, and proprietary market and customer data that is used or aids in marketing and selling goods or services to customers.

Multinational enterprise group (MNE group)

A group of associated companies with business establishments in two or more jurisdictions.

Multinational enterprise (MNE)

A company that is part of an MNE group.

Mutual agreement procedure

A means through which tax administrations consult to resolve disputes regarding the application of double tax conventions. This procedure, described and authorised by Article 25 of the OECD Model Tax Convention, can be used to eliminate double taxation that could arise from a transfer pricing adjustment.

Net profit indicator

The ratio of net profit to an appropriate base (e.g. costs, sales, assets). The transactional net margin method relies on a comparison of an appropriate net profit indicator for the controlled transaction with the same net profit indicator in comparable uncontrolled transactions.

“On call” services

Services provided by a parent company or a group service centre, which are available at any time for members of an MNE group.

Primary adjustment

An adjustment that a tax administration in a first jurisdiction makes to a company’s taxable profits as a result of applying the arm’s length principle to transactions involving an associated enterprise in a second tax jurisdiction.

Profit potential

The expected future profits. In some cases it may encompass losses. The notion of “profit potential” is often used for valuation purposes, in the determination of an arm’s length compensation for a transfer of intangibles or of an ongoing concern, or in the determination of an arm’s length indemnification for the termination or substantial renegotiation of existing arrangements, once it is found that such compensation or indemnification would have taken place between independent parties in comparable circumstances.

Profit split method

A transactional profit split method that identifies the relevant profits to be split for the associated enterprises from a controlled transaction (or controlled transactions that it is appropriate to aggregate under the principles of Chapter III) and then splits those profits between the associated enterprises on an economically valid basis that approximates the division of profits that would have been agreed at arm’s length.

Resale price margin

A margin representing the amount out of which a reseller would seek to cover its selling and other operating expenses and, in the light of the functions performed (taking into account assets used and risks assumed), make an appropriate profit.

Resale price method

A transfer pricing method based on the price at which a product that has been purchased from an associated enterprise is resold to an independent enterprise. The resale price is reduced by the resale price margin. What is left after subtracting the resale price margin can be regarded, after adjustment for other costs associated with the purchase of the product (e.g. custom duties), as an arm’s length price of the original transfer of property between the associated enterprises.

Residual analysis

An analysis used in the profit split method which divides the relevant profits from the controlled transactions under examination into two categories. In the first category are profits attributable to contributions which can be reliably benchmarked: typically less complex contributions for which reliable comparables can be found. Ordinarily this initial remuneration would be determined by applying one of the traditional transaction methods or a transactional net margin method to identify the remuneration of comparable transactions between independent enterprises. Thus, it would generally not account for the return that would be generated by a second category of contributions which may be unique and valuable, and/or are attributable to a high level of integration or the shared assumption of economically significant risks. Typically, the allocation of any residual profit (or loss) remaining after allowing for the profits attributable to the first category of contributions would be based on an analysis of the relative value of the second category of contributions by the parties, supplemented where possible by external market data that indicate how independent enterprises would have divided profits in similar circumstances.

Secondary adjustment

An adjustment that arises from imposing tax on a secondary transaction.

Secondary transaction

A constructive transaction that some jurisdictions will assert under their domestic legislation after having proposed a primary adjustment in order to make the actual allocation of profits consistent with the primary adjustment. Secondary transactions may take the form of constructive dividends, constructive equity contributions, or constructive loans.

Shareholder activity

An activity which is performed by a member of an MNE group (usually the parent company or a regional holding company) solely because of its ownership interest in one or more other group members, i.e. in its capacity as shareholder.

Simultaneous tax examinations

A simultaneous tax examination, as defined in Part A of the OECD Model Agreement for the Undertaking of Simultaneous Tax Examinations, means an “arrangement between two or more parties to examine simultaneously and independently, each on its own territory, the tax affairs of (a) taxpayer(s) in which they have a common or related interest with a view to exchanging any relevant information which they so obtain”.

Trade intangible

An intangible other than a marketing intangible.

Traditional transaction methods

The comparable uncontrolled price method, the resale price method, and the cost plus method.

Transactional net margin method

A transactional profit method that examines the net profit margin relative to an appropriate base (e.g. costs, sales, assets) that a taxpayer realises from a controlled transaction (or transactions that it is appropriate to aggregate under the principles of Chapter III).

Transactional profit method

A transfer pricing method that examines the profits that arise from particular controlled transactions of one or more of the associated enterprises participating in those transactions.

Uncontrolled transactions

Transactions between enterprises that are independent enterprises with respect to each other.

Unique and valuable contributions

Contributions (for instance functions performed, or assets used or contributed) will be “unique and valuable” in cases where (i) they are not comparable to contributions made by uncontrolled parties in comparable circumstances, and (ii) they represent a key source of actual or potential economic benefits in the business operations.